This post is part of a series of reviews I am writing as I continue my 12 Months 12 Books reading plan, which you can read more about here.

I started out my reading plan with a doozy.

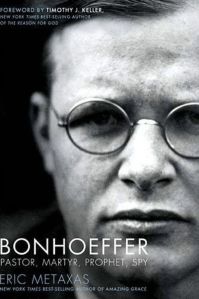

Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy by Eric Metaxas recounts the courageous but short life of the German pastor and theologian who was killed for his involvement in a conspiracy to assassinate Hitler. In terms of length, I do not expect any other book I read as part of the plan to match this one’s 624 pages. Despite its length, Metaxas has penned an immensely readable biography that combines a crisp pace with authoritative research and reflective narration.

Early Life

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was born in Breslau, Germany and raised within a remarkable family. His father, Karl, was the director of a hospital and a leading researcher in the field of neurology. His mother, a highly cultured and competent woman named Paula, stayed at home and impressed upon her children the beauty and joy of music, literature and especially the Word of God. Of all the children in the family, Dietrich stands out as perhaps most defined by his parent’s unique relationship. His father, while religious and upright to a fault, was not a spiritual man nor someone who would profess a belief in things beyond what was scientifically verifiable. His mother, on the other hand, was a strong woman of faith who despised hypocritical religiosity and trained her children to fear a living God. Despite their differences, both parents loved one another dearly and agreed on every aspect of their child’s upbringing. From this unique relationship, Bonhoeffer grew into a man who would demand a faith that was real,authentic, tested and true, and would despise a faith that was ineffectual, hypocritical, and “cheap”.

Bonhoeffer decided to become a theologian despite his father’s pleadings for him to pursue a career in music, where he was unnaturally gifted. But Dietrich was undeterred, and he began his studies in Berlin. Liberal theology had all but consumed Germany by the time Bonhoeffer reached the university, but it was Karl Barth, one of Bonhoeffer’s professors, who had the greatest effect upon Bonhoeffer. Against the prevalent historical-critical approach to the Bible, Barth “asserted the idea, particularly controversial in German theological circles, that God actually exists, and that all theology and Biblical scholarship must be undergirded by this basic assumption, and that’s that” (60). Scandalous. And for Bonhoeffer, life-defining. To the ire of other professors who adored him and his potential to be “great”, Bonhoeffer, with his prodigious intellect and drive chose the way of the fool. He moved on through his life convinced to the core that the Bible was a text that was of highest importance because God revealed Himself to man through it. At some point in the next few years, Bonhoeffer would acknowledge that this intellectual assent soon led him into a spiritual relationship with God and into new life.

The Plot

Bonhoeffer’s life might have been remarkable at any other time in human history, but he was a man called for a specific purpose in the age he was born. While Hitler and the Nazis began engulfing Germany in their hypnotic and aggressive ideology, Christianity in Germany had all but disintegrated into a lifeless religion of Aryan-worshiping idolatry. Bonhoeffer quickly to recognized God’s call on him to stand as a guardian of the church of Christ, even if it meant his death and, by the world’s terms, failure. But the highest motivation for Bonhoeffer was never success; it was obedience to God.

The Nazi “Christianity” that Bonhoeffer was declaring war against was horrifically anti-Christ. In the words of one of its spiritual leaders, “the insanity of the Christian doctrine of redemption doesn’t fit at all into our time” (165). Across the sea, Bonhoeffer noticed a similar shift away from Christian truth, although under a much subtler form. He remarked about his visit to churches in New York “that they preach about virtually everything; only one thing is not addressed[…], namely, the gospel of Jesus Christ, the cross, sin and forgiveness, death and life” (99). From this statement and others, and before we even get to his role in the assassination of Hitler, it is clear that Bonhoeffer’s greatest battle was not against man but against a Christ-less Christianity and the fancy of the times masquerading as Truth.

Naturally, Bonhoeffer’s active fight against Nazi ideology made him a target. While rarely vocalizing anything directly against Hitler because he knew of the likely repercussions, Bonhoeffer staunchly defended the Church against the rapidly growing tide of spiritual deadness propelled by Nazi control. Soon, Hitler achieved total power and the full reality of the horrors being committed underneath his regime became unavoidable, forcing Bonhoeffer to deal with a decision few pastors or theologians ever encounter: to fight the darkness in word and in prayer alone, or to put his hand to the plow and actually take an active role in the mutiny against Hitler. Dietrich did not easily arrive at his conclusion and he admitted other men of God might disagree with it, but he was utterly convinced that his course of action must be the one of unpopularity (even, perhaps, among Christians). He chose to take part in the Resistance, an undercover group of elites and high-ranking military officials committed to assassinating Hitler. Perhaps Bonhoeffer’s best explanation of his reason for joining the Resistance lay in his metaphor characterizing Hitler as a drunk-man on the road, foolishly slaughtering many innocents. For Dietrich, “it would be the responsibility of everyone to do all that they could to stop that driver from killing more people” (326).

Remarkably, Dietrich turned down numerous offers and chances to lead thriving ministries in America and England, choosing rather to obey the Lord’s call and remain in Germany where he would most certainly die. Two assassination attempts were carried out, but Hitler survived both of them by the most miraculous means. When one conspirator was captured, however, the names of the others were leaked and Bonhoeffer was detained. In his final days, Bonhoeffer, Germany’s most popular evangelist and saint, shared a cell with a former Nazi doctor who helped invent killing machines for concentration camps, a British Intelligence Officer, and a few other wildly different elites and political figures detained for real or imagined slights against Hitler. To this eclectic group, Bonhoeffer finished his minstry, sharing the Gospel and leading them in prayer.

Mere days before Hitler assassinated himself, and most likely by Hitler’s personal command, Bonhoeffer was retrieved from his cell and executed. The soldiers had come to take him the moment he had finished leading the prisoners in a Sunday service.

Conclusions

No other man of God that I have read about has convicted and connected with me like Bonhoeffer. Metaxas’ superb biography covers a dearth of information while remaining narratively spry. I very much enjoyed Metaxas’ comments, insight, and satirical wit throughout the book, particularly in his undressing of Nazi ideology an. While Hitler and the Nazis are an easy target, I imagine most biographers and historians would have described their actions, ideology and history with a distant, sterile, historical objectivity. Metaxas will have none of that, and calls it like it is: utterly, insanely, deplorable.

The legacy of Bonhoeffer is of obedience, dedication, and unfailing commitment to the Truth of the Gospel and God’s Word. For Bonhoeffer, the reality of God as revealed through the Bible demanded absolute obedience, no matter the outcome. A crucified Christ, hanging on a cross and deemed an utter failure by the world but the greatest success by God was the foundation on which Bonhoeffer based both his controversial decision and the whole of his life.

Favorite Quotes: “I can doubtless live with or without Jesus as a religious genius, as an ethicist, as a gentleman—just as, after all, I can also live without Plato and Kant. . . . Should, however, there be something in Christ that claims my life entirely with the full seriousness that here God himself speaks and if the word of God once became present only in Christ, then Christ has not only relative but absolute, urgent significance for me. . . . Understanding Christ means taking Christ seriously” (82).

Strengths: Comprehensive, engagingly written, highly relevant to a variety of moral and ethical issues confronting our culture, government and Church today.

Weaknesses: It’s length clearly will put off many potential readers, but unlike many biographies, I found very little that I thought could be cut out. It was just lean enough that any potential future “condensed” version would most likely err too much on the side of leaving out integral elements. However, if the length really is that much of an issue, you could always try out Metaxas’ more approachable “Seven Men: And the Secret of Their Greatness”, in which he provides cursory overviews of several reputable men, including Bonhoeffer.

Recommendation: I would recommend this book to pretty much anyone that can read without further qualifications.

[…] Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy […]